Morten Søndergaard was born in 1964 in Copenhagen. In 1992 he published his poetry debut Sahara i mine hænder (Sahara in My Hands). His poetry collection Bier dør sovende (Bees Die in their Sleep) was awarded the Michael Strunge Prisen in 1998. Søndergaard himself has translated several works of the argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges into Danish. From 2002 to 2007 he was the editor oft he magazine hvedekorn (wheat grains) together with Thomas Thøfner. As well as poetry, he has produced several sound installations, CDs and art pieces. His audio piece Monte Altissimo – Falling off the White Mountain, in which he worked with recordings from a piece of marble near the town of Carrara, was broadcast on Deutschlandradio in 2004. Most recently, the collection Døden er en del af mit navn was published in Danish.

Morten Søndergaard

They

to the sprechbohrer

Translated from Danish by Paul Russell Garrett

They are a small swarm, consisting of three bodies, three voices. The voices make the air move and the sound waves swarm our ears and we soon find ourselves in an acoustic trance. Are they singing or speaking? What are they saying and how are they saying it? They move between music and speech, non-music and non-speech. They resonate. They.

That small word is the starting point for my work They. Or rather the swarm of words which in language we call pronouns. As ever, a poem comes from many places, but I am able to pinpoint precisely one source of the poem They. It was a spring day during the pandemic, and I was with my girlfriend, watching a swarm of bees hanging from an olive tree. I’ve always dreamed of keeping bees and for the past five years I’ve kept five hives. But bees are given to swarming. It’s something they like to do. For bees, swarming is a sign of strength and great joy. They want to go out and pollinate the entire world. That day, we stood watching this remarkable natural phenomenon that is a humming swarm of bees. My girlfriend pointed up at the swarm and said: there it is. The swarm was in the singular. Suddenly it was clear that it was one animal, a superorganism.

When we work with bees we usually refer to them as them. Now they had become an it. The swarm, it hung from the olive tree: all the bees had gathered into one big warm clump of coruscating wings and bees with bellies full of honey. It. They sang with one voice. The transformation from they to it was magical for me. Because I’ve always been particularly preoccupied with pronouns. They’re difficult and heavily laden. And they often fly out of my sentences, so that I have to check the sentences to see if I’ve put them in the right places. When I created my Word Pharmacy – a concrete poem combining medicine and grammar – I based the various word classes on existing pharmaceutical preparations. For pronouns I used Prozac. Pronouns have the strongest side effects in language:

Fainting fits. Cramps. Can be serious. Awareness disorders. Loss of place. Loss of self. Dilated pupils. Ischuria (urine retention). This can be, or can become, serious. Speak to a poet. Edema (fluid retention), hypersensitivity. Hair loss. Increased sensitivity to sunlight, photosensibility. Minor haemorrhages in skin and mucous membranes. Panic attacks. Teeth grinding. Namelessness. Heightened risk of bone fractures. Aggressiveness. Sense of personal unreality or personal alienation. Loss of place. Loss of self. Loss. Pathological euphoria. Mania. Retarded ejaculation. Impotence. Orgasmic difficulties. Diminished sexual desire. Anxiety, confusion, indifference. Increased sexual desire. Lengthy, painful erections. Male lactation.

I’ve carved pronouns in marble and I’ve cast them in beeswax. For they are strangely hard yet simultaneously melting, incorporeal words. We encounter them every day in many different ways. Politicians warn: “It’s us or them!” or “We must stand together.” But who are we? Who are they? Billboards whisper smugly to us: “Because you’re worth it.” or “We work for you.” Some groups resist language’s predominant pronouns and ask to be referred to as they instead of he or she. In poetry you is used to address everybody, and poems can be weighed down by excessive use of the word I. Pop songs deal almost exclusively with the interchange of pronouns.

In grammatical hierarchy, pronouns are lieutenant in the etymological sense of the word: lieu tenant, one who holds the space. They hold the place of names. They’re there instead of the name, the person, the body. But the question is: what is left when we only have the word we remaining? What do we do when we only have a pronoun to go by? As if we were what remained after all other language melted away. We’re left with the sound of the pronoun we. We have to start again.

Where did we come from?

When it comes to language, we come from the side of sound. We are born without pronouns and without language, and we crawl our way to language through repetition. Walking home from school as a child, I would often start repeating words. I no longer remember the words I repeated, but they might have been hard words like “seismograph,” or “disestablishmentarianism” – difficult words we would learn in school. Or else small words I considered my own: “sun” or “chair” or “tree” or “smile.” But the result of the repetitions was that the words were transformed into a warm sound in my mouth. The word became a piece of chewing gum I could blow speech bubbles with. The neighborhood I lived in consisted of virtually identical houses, which perhaps inspired the repetitions. When I repeated words they sometimes lost their meaning. The content of the words was lost in the maelstrom of repetition, I moved from sign to sound. The uniformity of the neighborhood was underscored by the virtually identical street names: Blueberry Way, Raspberry Way, Mulberry Way; it was called the marmalade neighborhood. And so there I walked, in an attempt to delay or master the act of coming home from school, making my own acoustic jam.

Was this not a strange activity to take up? Talking to yourself is at best suspicious. Repeating yourself moves you to the world of the senile and the insane. The ghosts and shadows whisper the same few eerie sentences to us. They repeat us. Did I not want to go home? Were the repetitions meant to keep something all too familiar at bay? Whatever the case, the act of repeating words has had a strong influence on me ever since. Perhaps it’s because they have a soothing effect, like hearing the same song, the same story before you can fall asleep.

In more recent years, when I perform readings, I create two samplers that function as follows: I read poems into a sound machine, creating samples of words or lines of poetry that I can then repeat and vary. The loops that are produced are transformed into rhythmic structures that can be treated and I can then read new words and lines of poetry over them. The voice is a remarkable instrument, and in harmony with the samplers it can create an acoustic texture comparable to music. I don’t consider myself a musician, but I like to let my voice explore sonorous acoustic landscapes through repetition and treatment. I consider these readings to be more dissipations than recitations.

When you dissipate words through repetition and machines, it’s as though moving toward a pre-linguistic state. A state somewhere outside of language. Is this the way to think of it? That you were outside language, and the others, the language bearers, were inside? If so, I want to go back out again, out of the house of language and into the surrounding language-less landscape. In any case, we come to language from the side of sound. We are most likely born with some linguistic structures and a pre-programmed disposition for language, but we are language-less from birth and language is something that must be learned. As babies we can only communicate with sounds and tears. We hear and understand our first sounds as intonations, melodies, and sequences that we slowly learn to master. But we start somewhere outside of language. We fumble our way along the borders of language and only after many stuttering stops and starts are we inside the warmth of language. And once we’re inside, we can’t go out again. We enter the house of language through repetition. Testing and repeating we come closer, we babble and sing nonsense and loudly repeat our NO. We are corrected and we learn to pronounce the words. We make mistakes and we correct ourselves. Fail. Fail better.

Our brains most likely have a kind of linguistic inclination that makes us strong receptors for language. Yes, we are expected to learn to speak. It is expected for pronouns to settle in us, to end up inside us and hang in our brains like a linguistic bee swarm.

We come from the side of sound. And maybe that’s why the sprechbohrer and the way they treat language feels so intuitively right. They move us back to a state of prelinguistic existence. Once again we stand on the border of language, listening to it from the outside. What was word is now sound. It is the sound of language we hear when we listen to the sprechbohrer. In the same way as the bees move out of their safe and familiar hive, language is now out in the open. It has been exposed and made visible. It takes courage. It takes the courage that is necessary.

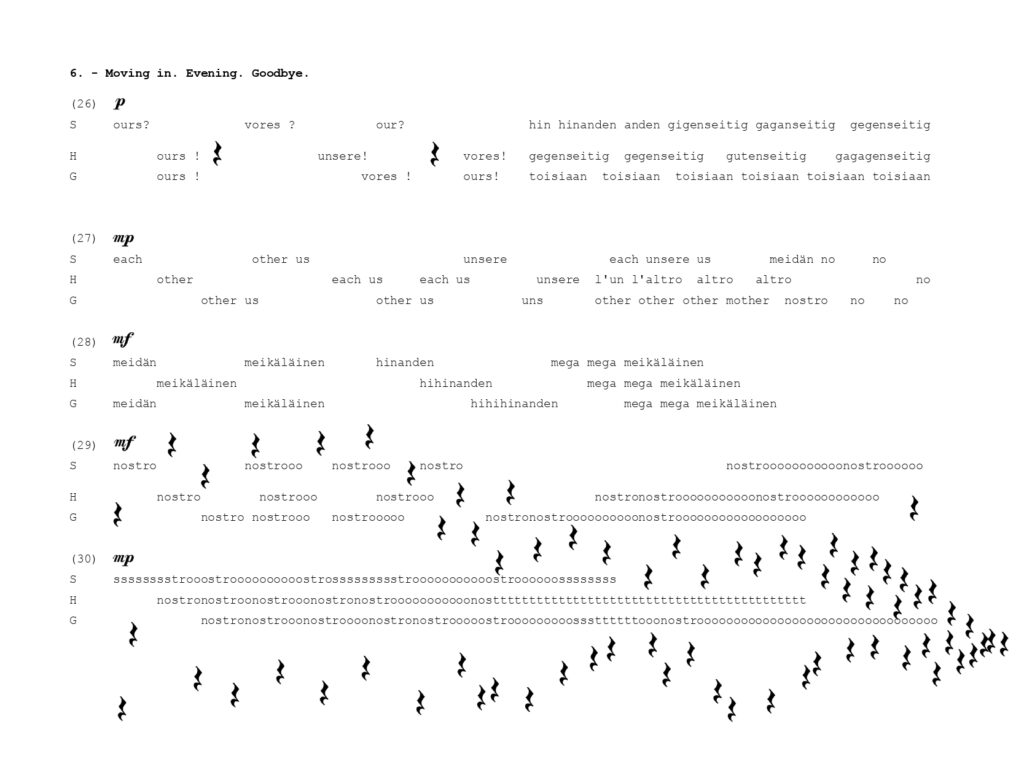

When bee swarms are out in the open, a remarkable negotiation takes place. The bees have to choose a new home and it is chosen democratically. A number of scouts fly out to search the area and return to dance excitedly for the rest of the swarm, each trying to sway their fellow sisters to choose their new dream home. It can be a hollow tree or a cavity in a wall. Other bees fly out to examine and inspect the places that have been campaigned for, then return and dance their assessment. The choice of a new home can last several days. But when two thirds of the swarm agree and dance their agreement, the hive flies off and moves to the new home. This is the narrative structure I have made as the starting point for my work They. This compositional principal follows the swarm structure of the bees. I draw upon Italian, Finnish, English, German and Danish in linguistic material that is made up exclusively of pronouns.

I remember the first time I had to read a bee comb. It was like looking at a sign system I’d never before seen. It was a map of time. A map showing time in its waxy consistency. But I also thought of the comb as music. A sheet of music noting tempos and pitches and the landscape outside of the hive. A shared rhythm and a breathing shared by every individual in the hive. Because the bee family is one and many at the same time. Bees may have no ears, but they have incredibly sensitive legs that translate every oscillation and vibration into bee language.

In many ways what makes the bees’ swarming unique is their shared goal. They want the same thing. They need the same thing. They are unified in their it. They search the landscape to find what’s best for the survival of the entire family. Humans could learn from this mutual and unified endeavor. The colony is one united in listening to its surroundings. It wants the common good. We too listen to signals and vibrations. But listening is something altogether different from exchanging information. Listening does not immediately involve an exchange. To listen is to wait. Without listening no community can be created. To commune is to listen. It is this endeavor we are confronted with in the company of the superorganism the sprechbohrer. For they generate a sound as yet unknown to us. Not song and not word. It is a strange – an ethical sound – that may be the sound of language at its truest.