Eduard Escoffet, born in Barcelona in 1979, is a poet and cultural agitator. He has worked in different facets of poetry (visual and written poetry, installations, oral poetry, poetic action), but he has focused his interests on sound poetry and poetry readings. He is a co-founder of the platform projectes poètics sense títol – propost.org. He was co-director of Barcelona Poesia (Barcelona International Poetry Festival) between 2010 and 2012, and director of PROPOSTA, a festival of sound poetry and contemporary poetry at the Centre of Contemporary Culture of Barcelona (2000-2004). He has published the poetry collections Gaire (2012) and El terra i el cel (2013), as well as the artist’s book Estramps with Evru (2011). Has published two records with the electronic music band Bradien, Pols (2012) and Escala (2015).

Eduard Escoffet

Ode to the Walking Class

Translated from Catalan by Timothy James Morris

The Atacama Desert, in Chile, is home to a giant dump that now contains over 100,000 tons of discarded clothing. Unwanted and, above all, unsold garments undertake a journey that transports them from Asian factories to clothes shops in America and Europe, before finally bringing them to the free port of Iquique, Chile, where any items that can still be sold are sorted out from clothes no longer judged to have any market value. It is this “useless clothing” that ends up in the vast illegal landfill in the Atacama Desert: amid the arid mountains and dusty tracks, discarded clothes pile up relentlessly into dunes and hills that are occasionally beaten down by raging fires but never held back for long.

Under the unrelenting gaze of the desert sun – and far from prying eyes – these garish mounds rise ever skywards, towering testaments to a consumer society that never ceases to grow at the expense of an exhausted planet. Global trade dynamics and the voracious demands of fast fashion are what drive this unsustainable system: items of clothing travel the planet without ever once being worn, and natural resources are squandered simply to keep the cogs turning. And all this in the context of a looming climate crisis – to which the fashion industry is one of the main contributors – and a major migrant crisis.

Right through this very dump, in fact, pass some of the walkers on an 8,000 km journey from Venezuela to Santiago de Chile, crossing Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. They stop here to pick up new clothes and shoes to replace the worn-out items they are wearing, which are practically all they possess. The desert welcomes two influxes of rejects: surplus goods transported along international trade routes, and migrants forced by the system of global inequalities to set off on foot in search of a better life. When they meet, they expose a glaring operating system error: the laws of global capitalism make it easier for clothes to travel across the globe than people, whose way is all too often barred by barriers and borders.

Since 2015, more than 5.5 million people have fled Venezuela. According to the Organization of American States (OAS), between 4,000 and 5,000 Venezuelans leave the country every day, most of them on foot, having run out of options for survival at home and with no other resources available to them. This is one of the biggest migrant crises in recent years, larger in scale than the Syrian crisis. Making their way across the Americas right now are two great pilgrimages of despair: one heading north – through Central America – and one heading south. As Venezuelans flee their country in droves, migrants from other countries in the Americas, as well as from Africa and even as far as Asia, arrive in search of the American dream.

On 1 December 2021, after a brief stop in Bogotá, I arrived in Cúcuta, a Colombian border town that is the first port of call for many Venezuelan walkers. I had been invited by the Fundación El Pilar to take part in the closing session at the third edition of Juntos Aparte International Meeting of Art, Thought, and Borders and would then stay on for ten days as an artist-in-residence. While I was there, I went to the border crossing on the Simón Bolívar Bridge linking Cúcuta with San Antonio del Táchira, across the River Táchira in Venezuela, where I could see for myself the great swathes of walkers streaming down the highway towards Bogotá; there are even road signs warning drivers to watch out for walkers at the side of the road.

To reach the Colombian capital, they have to walk some 600 km, including crossing the Andes and the Páramo de Berlín highland plateau, whose high attitude and near-freezing temperatures make it one of the most dangerous stages of the journey – it was given its name by a German traveler who was reminded of the weather back home. It was during my stay in Cúcuta that the concept of the walking class began to take shape in my head. After several years exploring issues such as degrowth and the act of walking as a form of resistance to the dictatorship of speed and the thirst for petrol, my eyes were suddenly opened to a situation that made me see the act of walking in a completely new light.

Great migrations invade our reality now more than ever: from walkers in the Americas – both those heading north and those making for South American metropolises – and migrants under- taking perilous crossings of the Mediterranean in flimsy, unseaworthy vessels to refugees from Syria and other conflict zones. Not to mention those now fleeing Ukraine. Behind the screens of our world there are millions of people walking, fleeing, leaving everything behind, even though they might have little idea of where they are going. In the meantime, surplus goods from the other side of the world travel with the greatest of ease and scant regard for the health of the planet. Global capital maps out the routes with a simple plan: bewitch part of the planet with the thrill of novelty, while condemning the rest to poverty. From the comfort of our own homes, at minimal cost, we can summon almost anything to be delivered from the other side of the world, yet we are not quite so happy when it is people on the move seeking a decent life: we are turning part of the planet and our own homes into impenetrable bunkers built on the despair of the rest of the world.

At the same time that class consciousness and working people’s hard-won rights are being steadily eroded in Europe and America, a new class has emerged fueled by desperation: the walking class. This piece is dedicated to all those who have turned the civic act of walking into an act of resistance and an act of faith. If the thing about walking that had always interested me in the past was its independent, non-polluting character – an activity free of any ties to capital that was also a means of challenging a world that worshipped at the altar of speed – my experience in Cúcuta made me look at it anew. This was the starting point for Ode to the Walking Class.

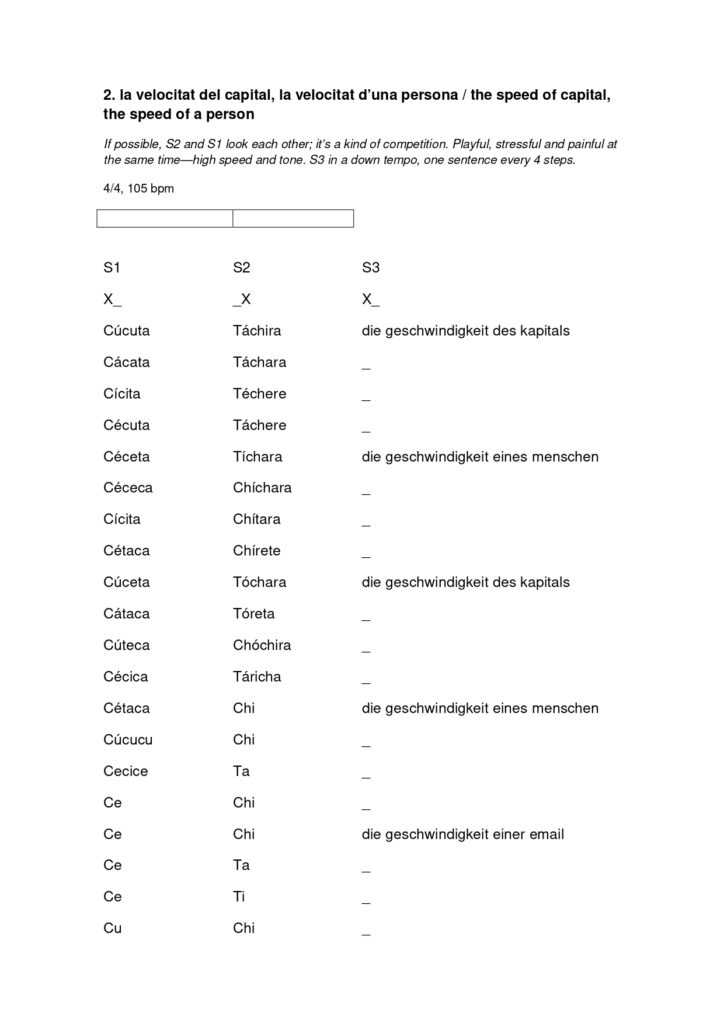

In this piece I have combined recited text and precise instructions with other, more abstract parts and have left room for the performers to improvise. I have also relished the opportunity to once again use cassettes. In total, then, this is a piece for six voices: three live and three recorded. I should also say that this is the first work I have written to be performed by someone other than myself. The fact that in this case the performers are sprechbohrer, a group I have keenly followed for many years, has only made the challenge even greater. For a poet like me whose work is rooted in performance and body, stepping outside my own voice to forge a dialogue with others, such as the members of sprechbohrer, is never easy, but the different paths that have led me to create this piece have been an undeniably powerful experience. I should like to thank sprechbohrer and Lettrétage for this unique opportunity to explore such a delicate subject from a space of complete creative freedom, halfway between music and poetry. All that remains now is to start walking and see where our feet take us.